A pacemaker at age 10

A rare condition caused Addison’s heart rate to drop to 15 beats per minute.

Article Author: Juliette Allen

Article Date:

Addison Slater had dreams of a summer filled with pool parties and playing with friends. But it turns out, the 10-year-old's heart just wasn't in it.

"In our minds, everything was fine until this summer," Addison's mother, Alicia Slater, said. "And then all of a sudden, our daughter has a pacemaker."

Geneticist confirms Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) diagnosis

Addison passed out for the first time when she was just 2 years old. Three years later, it happened again, this time accompanied by a seizure. As Addison grew up, the episodes continued, and she also suffered from excruciating pain in her hands, legs and feet. She never seemed to have as much energy as her friends.

Slater took her daughter first to her pediatrician, then to a pediatric cardiologist who suspected Addison had Elhers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), a connective tissue disorder often associated with heart problems. A geneticist confirmed the diagnosis of EDS and Addison was referred to see a pediatric electrophysiologist at Wolfson Children's C. Herman and Mary Virginia Terry Heart Institute.

Tilt table test reveals critically low heart rate

Addison was immediately scheduled for a tilt table test the very next day. In a tilt table test, a patient is secured to a table while lying down. The table then slowly tilts up to a standing position to see how the heart responds. During the test, Addison's heart rate dropped so low, doctors could barely feel her pulse. When the heart beats so slowly, it can't supply blood or oxygen to the brain, which may lead to life-threatening seizures.

"It was like this huge wave just crashed down on us," Slater said of receiving the news about Addison.

The solution was a pediatric pacemaker, but cardiologists and Addison's parents wanted to delay surgery until it was absolutely necessary. In the meantime, Addison was outfitted with an injectable device called a loop recorder, which relayed real-time data to software that doctors could access at any time.

Loop recorder helps doctors monitor heart data

For the first few weeks, Addison didn't have any concerning episodes where her heart rate dropped dangerously low. Addison was doing well enough that Slater took both her and her young son, Sullivan, on a family trip to Alabama. That's where things took a frightening turn.

"Addison was exhausted after the day of travel and her legs and feet were hurting, so I suggested we try some pressure points we had learned to relieve the pain," Slater said. "I just touched her ear, and she passed out. It was the worst episode she had ever had. Her freckles disappeared, the color in her lips disappeared and her whole body went white. Then she had a seizure and she wouldn't wake up."

Because Addison was outfitted with the loop recorder, her doctors were able to immediately pull up her heart data.

"Addison's heart paused for five seconds and the seizure was caused by lack of oxygen to her brain," Slater said. "Her pulse after that was around 15 beats per minute." That's an average of one beat every four seconds, which can be deadly.

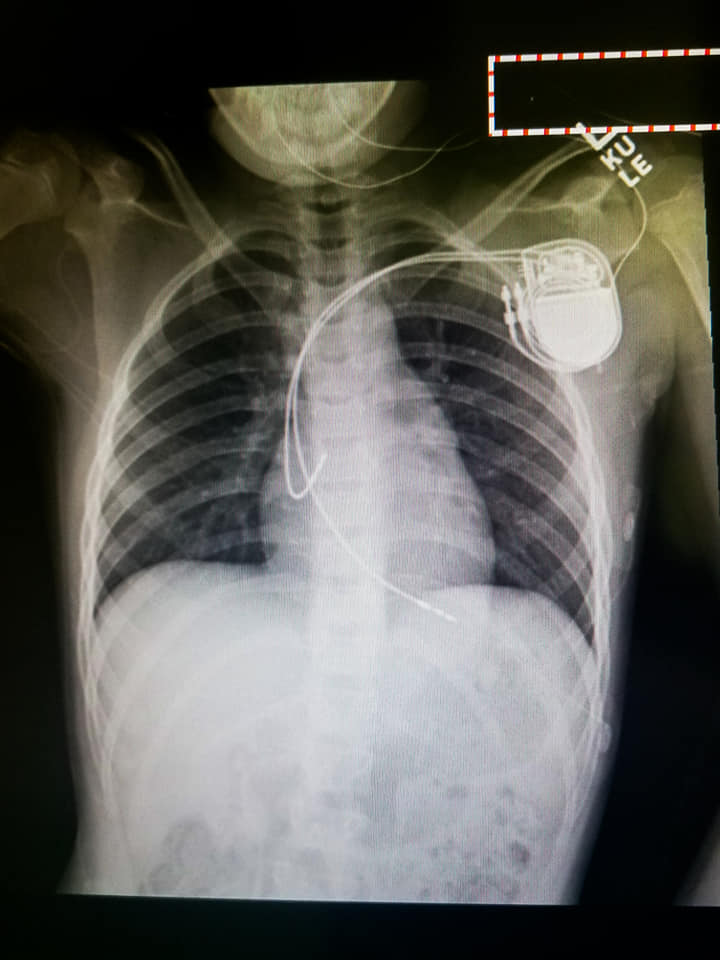

Pediatric pacemaker surgery performed at Wolfson Children's

In early July 2019, Addison underwent pediatric pacemaker surgery in the Cardiac Catheterization Lab at Wolfson Children's Hospital. She was able to go home after an overnight stay in the Wolfson Children's Cardiovascular Intensive Care Unit.

While Addison had to recover from the heart procedure itself, she shouldn't have any long-term limitations from the pacemaker. In fact, it should allow her to have the energy to keep up with her friends. For Slater, the pacemaker provides peace of mind that her daughter will be OK.

"If they hadn't done that tilt table test to realize how bad Addison's condition really was, my daughter might have gone to bed one night and not have woken up the next day," Slater said.

Find a pediatric heart specialist for your child

While Addison's exact condition is rare, other heart rhythm disorders are more common in children. The C. Herman and Mary Virginia Terry Heart Institute treats heart rhythm disorders ranging from atrial fibrillation to Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. To learn more, call 904.202.8550.